Many of us, myself included, use a smartwatch that shows us our pace while we’re running, such as a Garmin, Coros, Apple Watch, Polar, or another of many available brands.

First of all, there are many positives of having our pace right there on our wrists during runs, so let’s briefly discuss how it can be beneficial.

➡️Maybe you have a coach who programs your workouts using pace (i.e. a 30-minute recovery run at a 10:30-11:00 minute per mile pace), so you have data to help guide how easy or hard you’re running.

➡️Maybe you have a goal time for an upcoming race, so you use the watch to help you stay on track to hit that pace and time.

➡️Maybe you don’t use pace to guide your runs, but you like to analyze your progress as a runner from time to time.

Another great instance of a watch’s benefits is at the start of a race, when you’re surrounded by others, adrenaline kicks in, and you feel like you’re running much slower than you actually are.

Here are two instances when this affected my own races:

Adirondack Distance Run, 2012

One of the first road races I ever did was a 10-mile run with my dad while on vacation in Lake George (RIP Adirondack Distance Run). I didn’t use a watch that had pace at the time, and I started the run excitedly and confidently among the other few hundred participants.

After a half mile or so, my dad caught up to me and, glancing at his own smartwatch, half told/half warned me, “Dina, you’re going an 8:30 pace!” (At that point as a newer runner, the fastest race I’d done was around a 9:30 average, and that was fairly challenging for me.) I was surprised, but I shrugged, told him, “I feel good!” and kept going.

And then, a couple miles later…I died. Every muscle in my legs became sore, my hips hurt, my ankles hurt, and I felt blisters developing all over my toes. With a stubbornness many of us athletes possess, I ran the whole race without stopping, but my pace slowed dramatically and it was a fight until the end.

The following year at the same race, I had my own smartwatch and employed the opposite technique; I used my watch to ensure I started the race around a 10:30 pace instead, and slowly built it up faster and faster, progressing to finishing around an 8:30 pace, and my time was almost exactly the same to the second as the previous year. And thus, my signature move was born (negative splitting long races and setting smaller distance PRs at the end).

IRONMAN Lake Placid, 2017

The day before my first full Ironman, I attended a breakfast where athletes were given a presentation about details of the course and tips for the race.

One of the tips was regarding the start of the run; we were warned that we’d likely take it out too fast, especially because it began with a long downhill stretch. We’d think we were running easy, but the number on the watch would actually show us we were going much quicker. The presenter, who had a strong Boston accent, warned us several times to slow it down and “trust the Gahmin.”

I didn’t trust the Gahmin. I did look at it at the start of the run, noticed my pace was about 30-45 seconds per mile faster than I’d wanted to start the run, but chalked it up to running downhill and justified it, again, by thinking that I felt pretty good.

The consequences weren’t as atrocious as they were for the 10-mile race, but I definitely paid for it later on with very, very sore muscles for the second half of the marathon, and more walking than I’d wanted to do.

Those are a handful of reasons why your watch can be an excellent tool when it comes to pace. However, that’s not always the case; the watch can’t always be trusted.

Say I program a run for one of my athletes during which the first 10 minutes are at an “easy” pace, which for them is 9:45-10:00 minutes per mile.

What happens when they hit a hill 5 minutes in and their pace drops to 10:45, but their effort level is the same? Or when they reach the top and there’s a downhill on the other side, so they find themselves running a 9:00 pace without trying any harder? Are they supposed to overexert during the warm up to stay under a 10-minute pace, or slow way down on the downhill?

Hills are the perfect example of when sticking to the numbers on the watch, or in the programmed workout, just doesn’t make sense sometimes.

Powering up a steep hill in order to keep that 9:45-10:00 pace is no longer that athlete’s “easy” pace; it’s probably fairly strenuous. In that sense, “pace” is no longer a number; it’s an effort.

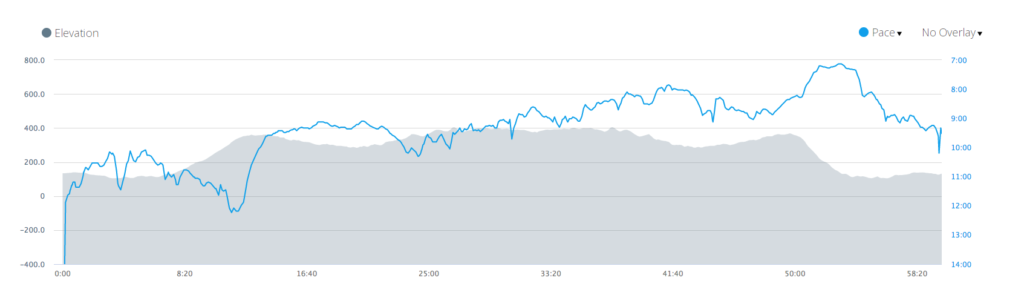

Take a look at this data from one of my runs. The gray background is the elevation, and the blue line is my pace.

The format of this particular run was a progression run. I started out nice and easy, then increased my pace gradually throughout the middle chunk, and then cooled down at the very end.

As you can see, the blue pace line does not depict a linear progression. My pace goes way down shortly after starting, and you can see it’s because I’m climbing a rather large hill.

Even though the pace in middle section is trending upward overall, there are plenty of ups and downs within, largely correlating with changes in elevation.

Finally, toward the end, my pace shoots up – I wasn’t booking it or going all out, I was simply running back down that same large hill from the beginning.

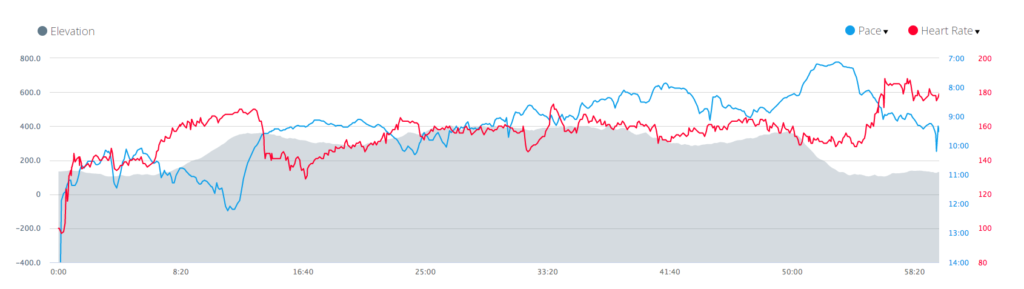

Next, let’s take a look at that same chart, but this time with my heart rate also displayed in red.

Adding in heart rate further shows how pace can become an effort, not a number.

During that first uphill, my heart rate jumps up, even as my pace falls. Typically, such a pace of between 11:00-12:00 minutes per mile would be a super easy recovery effort for me, but my heart rate proves that it was actually quite challenging, and it was because of that hill.

The same is true for the downhill at the end. My pace is a little over 7:00 minutes per mile, which would typically be a very hard effort for me, but my lower heart rate again proves that I wasn’t pushing extremely hard, just going down a steep hill.

Elevation is a big factor when it comes to why the pace on your watch doesn’t match your typical effort level, and probably one of the more common ones depending on where you live, but of course it isn’t the only factor. Here are a few others to keep in mind:

➡️You didn’t sleep well the night before – tired and sluggish legs might not be fully recovered, your heart rate might be elevated, and you might simply not have the same amount of energy as usual.

➡️You’re not fueled/hydrated enough – personally, if I’m hungry, my heart rate goes up. Lack of fuel and hydration can absolutely affect energy levels among other things.

➡️It’s 80+ degrees and humid – my athletes on the east coast have been experiencing this almost daily this summer. Heat and humidity slows you down, very similarly to how running up a hill slows you down. It’s common for runners to need to adjust their pace and their expectations simply because of the weather conditions.

➡️You lifted yourself into oblivion the other day and now you have mad DOMS all up in your hamstrings (anyone else? Just me? Ok.) – as you might think, we tend to feel better and stronger on fresh legs, as opposed to ones with lingering muscle soreness.

Watches are excellent tools, but sometimes they lie to us.

Remember, pace isn’t just a number, it’s also an effort. If you’re frustrated because you’re not hitting your paces one day, consider the above factors, because it’s very likely one or more of them is coming into play.

If you’re a newer runner, over time you’ll become more accustomed to how each of these factors affects you personally, and in turn you’ll know what to expect for your pace.

Listen to and learn to trust your body, not just the technology.

Happy running!

-Dina

Dina Grimaldi is a triathlon coach, nutrition coach, & personal trainer who helps athletes reach their goals while finding the balance they need to fit training comfortably into their lives; who guides those with nutrition or health goals to cultivate a lifestyle of sustainable habits and a healthy relationship with food; and who supports others through functional strength training and performance to become strong, healthy, and confident individuals throughout their lives.